#ecig: How Social Media is Changing the Ad Game

Tobacco advertising often evokes images of the Marlboro man or Joe Camel: old-school print ads that drew crowds both young and old. However, today’s advertising is different, and more camouflaged — you may not even blink as you scroll through your Instagram feed and pass an ad for e-cigarettes. Your favorite YouTube star might be hawking them through sponsored ads, or you may see creative and clever memes related to vaping.

Thanks to laws enacted largely in the 90s, advertisers were not only required to disclose the harmful effects of tobacco use, but were required to follow strict marketing guidelines. As a direct result, there was a dramatic decline in tobacco use — particularly among high schoolers.

Today, we’re seeing the landscape repeat itself – this time with e-cigarettes. “It’s healthy,” the advertisements claim. “It’s vapor, not nicotine.” A panel of experts in the legal, advertising, and substance abuse field gathered at JWU Providence to talk about the effect of such advertising on the legal landscape and on its youngest consumers for the seventh annual Law & Technology Symposium.

Daniel Less, assistant attorney general in the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office, Larissa Swenson, substance abuse prevention program coordinator at Easton Wings of Hope, and Elizabeth Carey, associate professor of marketing in Johnson & Wales College of Business, comprised the panel of experts to discuss this timely topic. Moderator Colleen Less, professor in the humanities department, asked each panelist to weigh in on questions with their unique professional lens.

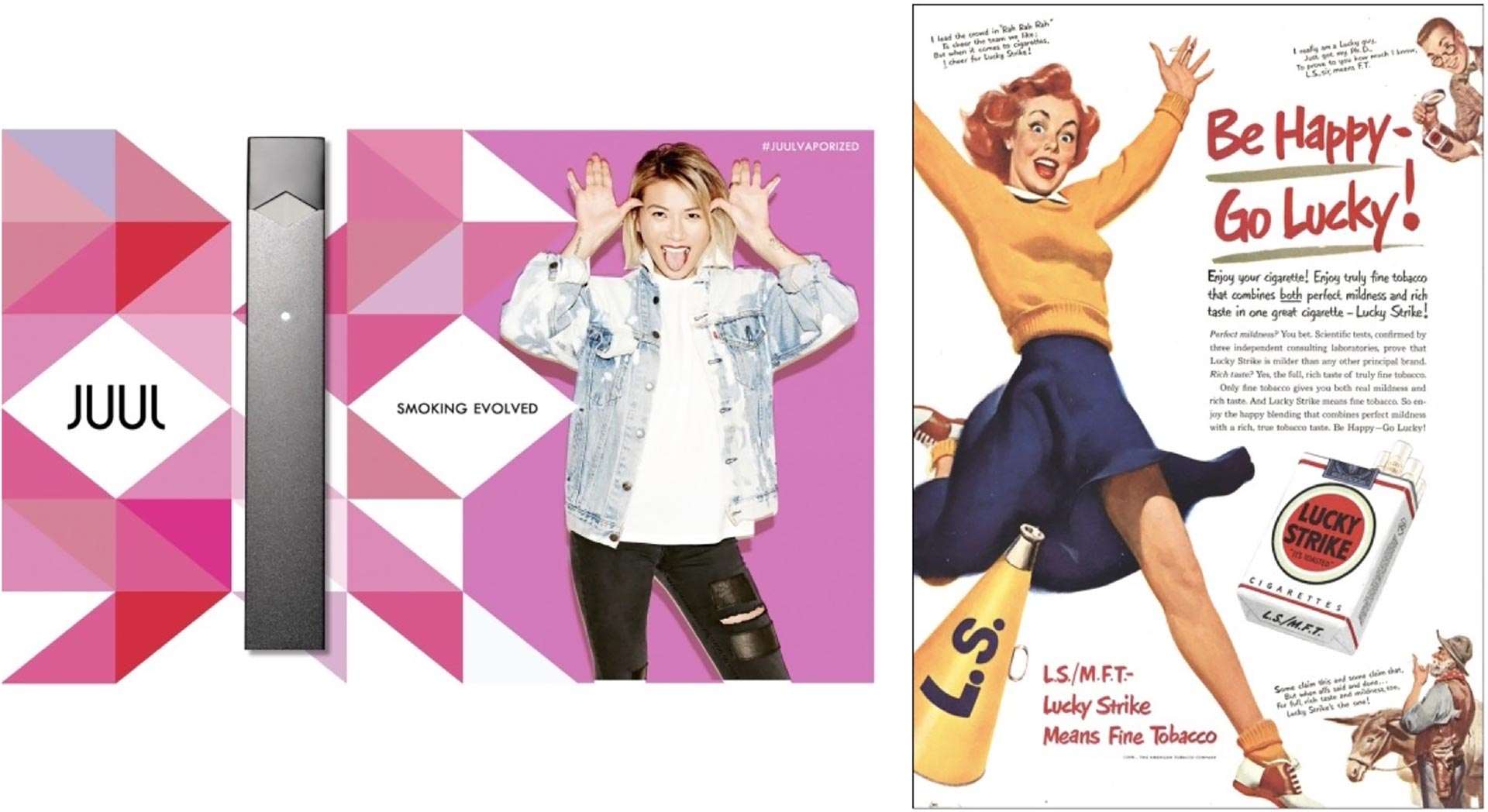

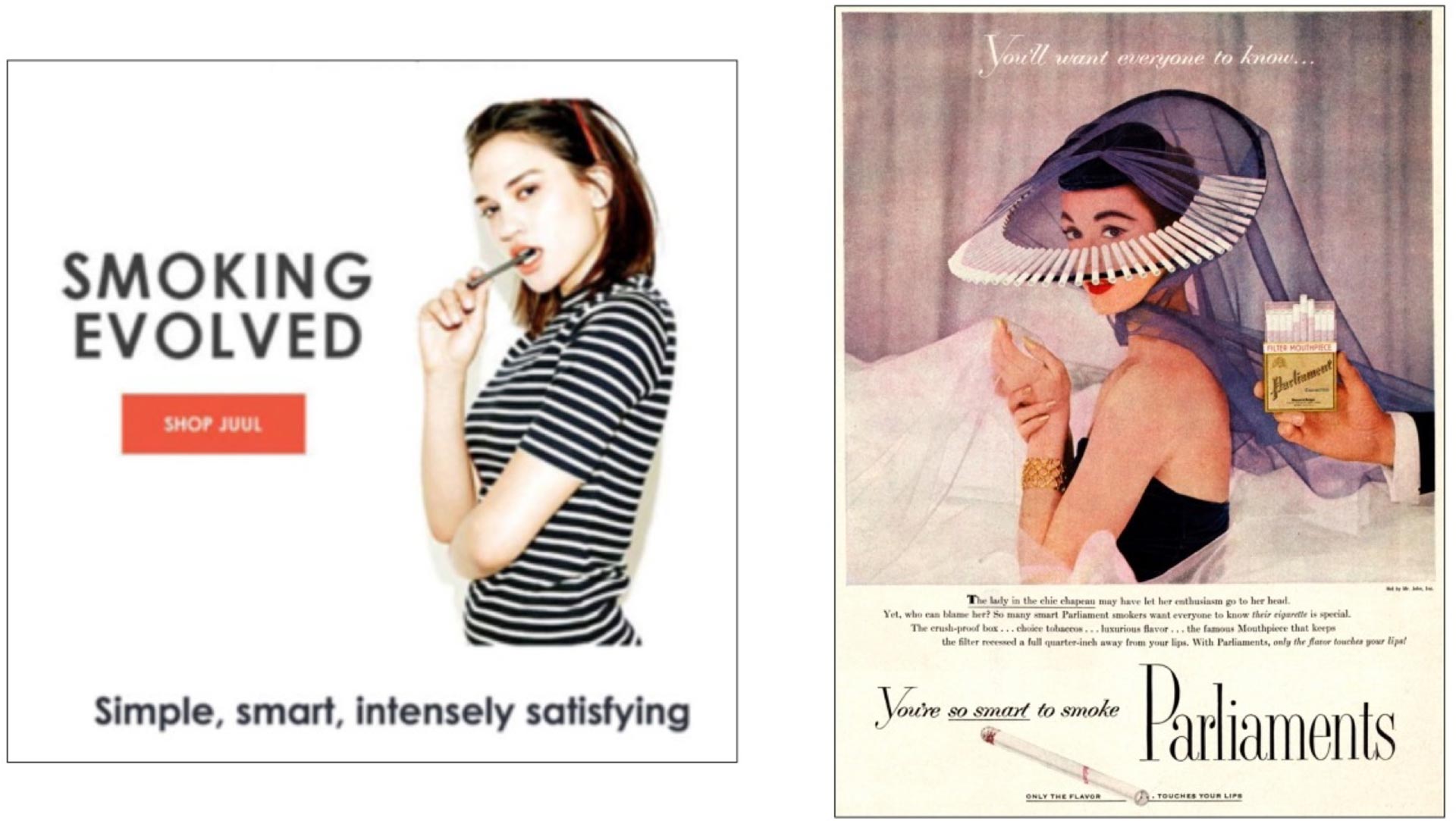

As a legal professional, Less is familiar with the sometimes-shady tactics e-cigarette companies use to market their products. He shared these tactics with the audience, pointing out the stark similarities between advertisements of the tobacco age and social media ads today. The tobacco laws enacted in the 90s don’t apply to these products, he explains, because they’re not yet classified as tobacco products. “The FTC is looking at the paid social media ads,” he says, “but it’s vast and ever-changing.” The unstable landscape of social media marketing means that lawmakers are always a step behind.

There are additional dangers to marketing these products through social media, Carey adds. Although there are laws in place that don’t allow advertisers to target anyone under the age of 13, Carey knows that minors often sign up for social media profiles when they are as young as 10. And the makers of e-cigarettes are not bound by restrictions. “Just like any other company, they can mine data, target based on demographics, and use influencers to sell their product.” E-cigarette companies even offer college scholarships and market and target those to early high-school aged kids.

"[Companies] can mine data, target based on demographics, and use influencers to sell their product."

Swenson clarifies the dangers of using technology to market these products because they are simply not safe. “You’re not getting tar [with e-cigarettes], but you are getting aerosolized vapor,” she states, “which goes deeper into your lungs. These vapors contain chemicals — including nicotine — that are harmful.” The focus on youth marketing is apparent, she adds, since the liquids come in flavors such as cotton candy, SweetTarts, bubble gum and more.

While the landscape is unsettling, Less acknowledges that the advances in technology are also helping companies with age verification software. “Juul has done a good job with it,” he says. When a user inputs his name, date of birth and town, Juul’s site makes the user wait while the public records are searched to verify that the person ordering is at least 18 years of age. When Less finds a website that doesn’t have these restrictions, it’s his job to serve a cease-and-desist — and ensure they actually do.

The group of students in the audience, with majors ranging from Marketing and Business Studies to Liberal Studies and Psychology, asked thoughtful questions of the panel that represented their wide-ranging interests. The discussion started with the tactics companies use to market these products to the use of products themselves. One student asked the panel if they thought e-cigarettes were a fad, specifically because the marketing is repeating itself and since tobacco use dropped, use of e-cigarettes might also.

“It can’t be a fad,” Less says simply, “because it’s addictive.” The other panelists agree, noting that while technology of today complicates things, the largest demographic of e-cigarette users are young people. Between the compelling marketing along with the addictive substances, it’s not likely to be a quick fad product. The discussion also touched on internet regulation to reduce the use of products — a hot-topic issue that toes the line of restricting freedom of speech.

While the digital landscape around marketing is ever-changing, and the use of the products themselves cannot be considered safe, the panel did not have a doom-and-gloom outlook. “As long as we keep having these important conversations with our children and our students, we can stay informed,” Carey says.