Making a Difference: Jonathan Harris Wins First Place in Design Competition

To Associate Professor Jonathan Harris making a difference to improve the community where he lives matters. As an industrial designer, he sees possibilities where others might only see problems, and he uses his creativity to come up with solutions. This May, Harris’ passion earned him, and a team from the Horsley Witten Group, a first-place win, and a $10,000 prize, in a design competition with the goal of finding a way to reuse the Crook Point Bascule Bridge in Providence’s Fox Point neighborhood.

“I first moved to Providence for grad school in 1997,” says Harris. “Soon, my wife Noelle and I fell in love with the scale and access that came with a pre-colonial settlement. We decided to stay and make a home here — the scale of the city and state left us feeling like we could make a difference. A 1:1,000,000 ratio is so much more comfortable than the 1:5,500,000 we had in Minnesota.

I feel elation, a sense of pride and warmth.

”[During my career] I have worked to make communities and places more comfortable and responsive to pedestrians and their needs. This is a great opportunity to apply the years of lessons I have learned. My ultimate dream would be a city designed around the pedestrian — what’s old is new again. [In winning] I feel elation, a sense of pride and warmth,” he adds.

The Crook Point Bridge, as it’s also known, has been sitting unused and in an upright position since 1976. A fixture in the Providence city skyline, the bridge is loved by Rhode Islanders everywhere. However, in 2019 the Rhode Island Department of Transportation (RIDOT) allocated $6 million to demolish the bridge in 2026-2027.

“At that point, I thought ‘why don’t we just look at alternatives for what we could do with the bridge.’ I live in that neighborhood, and it’s such a landmark for that part of the city and East Providence, that it seemed like a big loss,” Harris says.

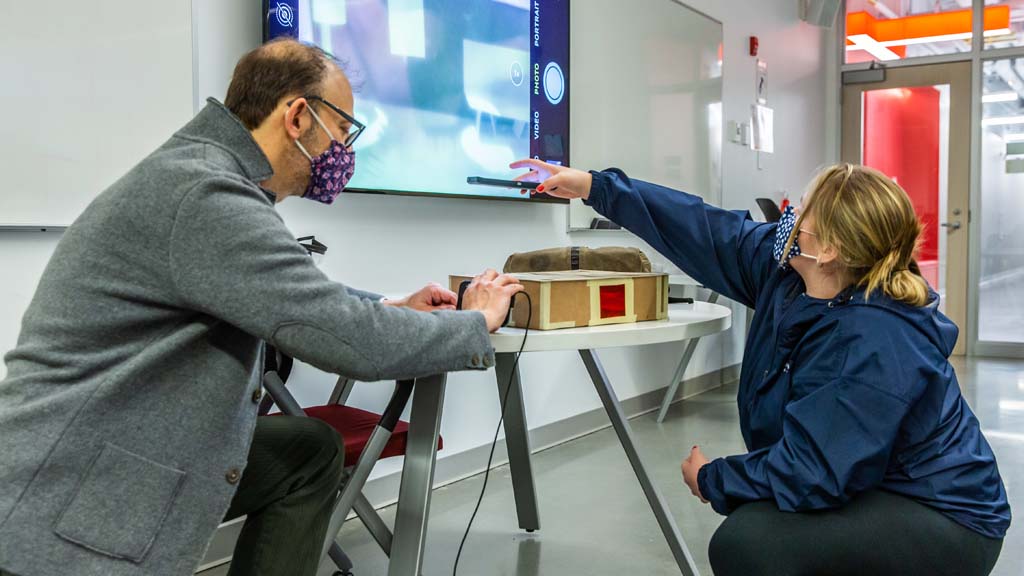

Harris got in touch with someone in the city’s planning department and suggested that he could have one of his studio classes, as a project, work on finding ways to reuse the bridge. They liked his idea, and soon students began conceptualizing solutions on how to reuse the infrastructure.

“They came up with some fantastic ideas,” says Harris of the student work. He presented the student ideas to the city, but says at that time they did not move forward with the project. However, later the city announced they would run a competition soliciting professional designs.

That’s when Harris decided to work on his own proposal, with the help of Jon Ford, P.E., and Ellen Biegert, RLA, from the Horsley Witten Group, and submit it to the competition.

“When I put together the group, I knew we needed a landscape architect and a civil engineer,” says Harris. “And the best civil engineer I know is Jon. He suggested Ellen join the team, and she turned out to be an amazing powerhouse.”

As they set out to develop their concept for the bridge, Harris remembered that one student, Sabrina Alpino ’20, Engineering Design & Configuration Management, developed a student concept which included keeping the upright portion of the bridge separate from the decking. “That was an amazing idea and we asked Sabrina if we could use [that part of it] in our design, and she said ‘absolutely,’” Harris adds.

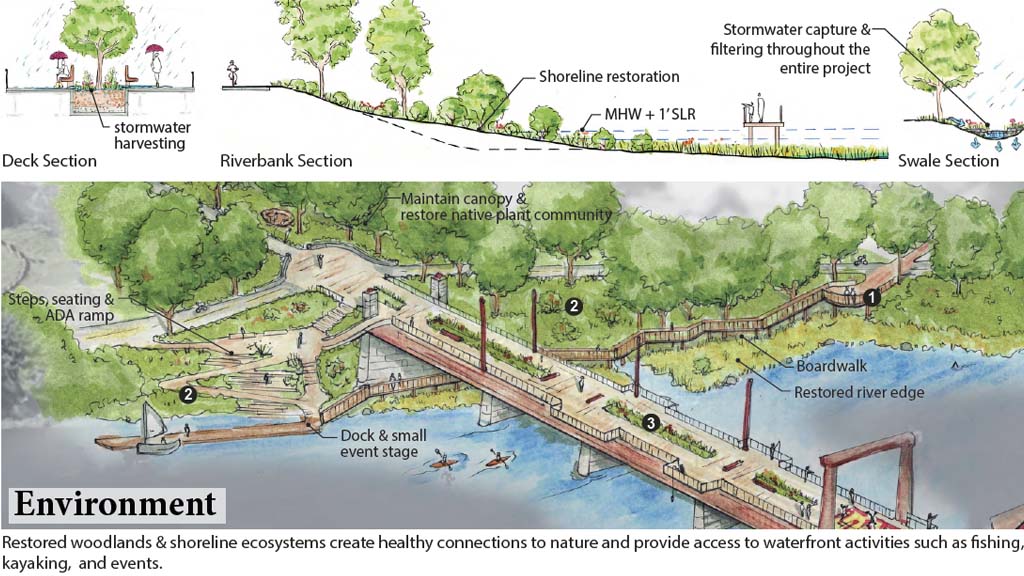

On their design’s plan board, the team describes their approach for reusing the bridge, as a way to: “strategically create a series of unique riverfront public spaces to physically and visually connect people to both a restored riverbank and to a celebrated bridge structure. The Bascule Bridge is an icon seen for miles, a reminder of the strength and tenacity of our forebearers. It is inspirational, shifting over time from utility to art. This feature promises a new transformation, in which the bridge becomes a lit beacon, a canvas for artists, and a reflection of our always changing community.” In addition, they note, their design hopes to integrate the park, river and bridge into the surrounding neighborhood, to draw people in and through the area.

The Providence Redevelopment Agency, the agency sponsoring the competition, took note of the team’s design, selecting it as one of the top five semi-finalists out of 80 proposals submitted in 2020. Now that their design has been chosen as the winner of the competition, the City of Providence, along with the Redevelopment Agency, hope to drum up support to preserve the bridge and revitalize the area by creating connectivity to the Fox Point neighborhood and the waterfront. Harris is hopeful the project will move forward, but understands that it might take some time.

“I’ve worked in this field long enough to know that nothing happens in a year or two, I mean there’s so much involved. My job is essentially done once I do the design, because that’s what I can control. A big part of being a designer is accepting that when you submit something,” he says.

Contributing Where He Can

This way of thinking about projects seems to help Harris stay focused on what’s next, and he’s usually busy trying to contribute as much as he can to the big picture. “I respond to what’s out there,” he says.

He’s the principal at Transit Matters, a company he started in 2006 to focus on supporting walkable communities by “providing the tools to reclaim a lost public realm, the street, for all users.” He has dedicated a lot of time to re-envisioning bus shelters around the state, and has so far designed some for Wickenden Street, Wayland Square, Fox Point, and Hope Street, all in Providence, and one in East Greenwich. He’s also working on one for Central Falls.

“I guess every one of them is about that community,” says Harris. “I try to give them a new place for their identity. Most of my shelters you can walk through, I really feel that that’s important. It’s a place to be in a community spot, so I want them to envelop the community as much as possible.”

He’s also designed a solar powered information kiosk located downtown at the Providence Rink and solar powered street lights. In 2016 Rhode Island Monthly awarded him and his team a Rhode Islander of the Year Award for the street light project they installed on Hope Street as part of the Off-Grid on Hope project.

In addition, Harris is very vocal about any transportation related project shaping up in the state. Most recently, he was part of a group that presented an alternative to the Route 6 and Route 10 highway proposing to transform it into a boulevard. The proposal, called “Moving Together,” suggested providing more efficient transit options which would include separate two-way bus and bike lanes, more walking paths and expanded green spaces.

“In the end they changed their design process and they came up with something better than they were [originally] going to do. They didn’t get as far as we had hoped they would, but we did change the conversation on that,” he says.

Walking Toward Inspiration

Growing up, Harris spent time in Ohio and Minnesota before moving to Wisconsin to attend the University of Wisconsin – Madison. The experience of living in the various environments contributed to his outlook on communities and walkable cities.

“I spent 10 years in Ohio where there were bike lanes behind communities and I could walk to school. And then when I got to the suburbs in Minneapolis, you couldn’t really get anywhere unless you rode a [car or a] bike, and there weren’t any bike lanes for us and no sidewalks — but I mean, I rode a bike and didn’t think twice about it,” he says.

“I think the biggest change for me, or when I really noticed it, was when I went to undergrad at the University of Wisconsin – Madison, which is a long, big campus with lots of walking. It’s actually detrimental to own a car there, you’re not driving anywhere, you’re walking. And that sort of connection to the community, to the people and to the location was really it for me; it really hit me at that time that this is really important,” he adds.

It was there that I realized that I really wanted to focus on this sort of linchpin between movement, community and identity.

Later on, he moved to Rhode Island to attend graduate school at the Rhode Island School of Design, and that solidified his thinking even more. “It was there that I realized that I really wanted to focus on this sort of linchpin between movement, community and identity,” he says. “I go back to some of those ideas [in my thesis], that’s where I started working out some of the concepts; your thesis kind of becomes the groundwork for everything you do later.”

Taking It to The Classroom

At JWU, Harris shares his passion with his students by having them work on assignments where they focus on people and their needs first. A project-based instructor, he’s had students work on designing a friendlier street bench; custom-building a bike food-cart for a client; conceptualizing ways to reuse the Crook Point Bridge; coming up with vehicles which are more user friendly and accessible than the ones we have today; finding solutions for work from home office set ups created on the fly due to Covid-19 restrictions; looking at how redlining practices in Providence neighborhoods contribute to, among other things, a lack of trees in the city and how better design could improve that, and many other projects.

“I tend to bring a lot of these projects to my classroom, I just can’t help it,” he adds. “These classes give students the opportunity to really explore different topics. We’re not an urban design program, but there’s so much to learn in an urban design situation that there’s no problem bringing in these ideas.”

With his class assignments, Harris aims to give students the tools they need to be more creative. “I like to push [students] to places that are uncomfortable [in the design world,]” he adds.

“Usually if you’re in your comfort zone, you’re doing things you already know. I really like to push them past the point of comfort into an uncomfortable zone. In design that’s something you have to learn to live with. You’re often in a place of unknown and uncertainty and you have to sort of dig your way out of there somehow to find solutions.”

This is his approach to design, and he is counting on his students to take it to heart — because after all, there’s always more to do. “Once you’re a designer, you’re always a designer, you find it everywhere. It’s like you can’t live your life and not be a designer once you experience it.”