How Can Gen Z Transform U.S. Politics?

Kurt Cobain once said, “The duty of youth is to challenge corruption.” This sentiment applies well to Gen Z’s values, according to the spring edition of JWU Providence’s Media & Politics Cafe: “Political Change, Political Discourse and Polarizing Practices: How Can Gen Z Transform U.S. Politics?”

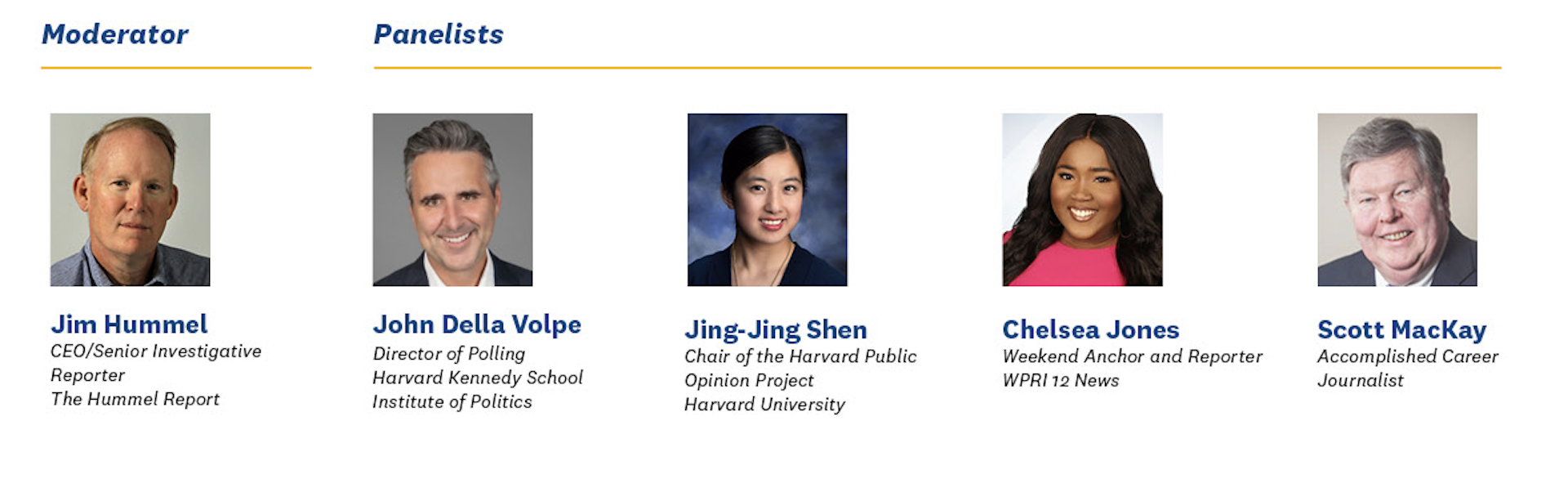

Moderated by Jim Hummel, CEO and senior investigative reporter for “The Hummel Report,” the panel featured

- John Della Volpe, director of polling, Harvard Kennedy School Institute of Politics; author of “Fight: How Gen Z is Channeling Their Fear and Passion to Save America”

- Jing-Jing Shen, chair of Harvard Public Opinion Project, Harvard University

- Chelsea Jones, weekend evening anchor and reporter, WPRI 12 News

- Scott MacKay, accomplished career journalist

Gen Z Explained

Gen Z, or “Zoomers” as they are commonly called, are born between 1997 and 2012 and are currently between the ages of 10 and 25. According to Della Volpe, “Everything we thought we knew about this generation was wrong.” He notes that although Gen Z has becoming subtly more progressive than their Millennial counterparts over the past 15 years, they do not abide by traditional labels. For example, Gen Z Republicans’ views on gun rights have shifted 20 points. Also, regardless of political affiliation, Gen Z is more conservative than their parents about school choice.

Zoomers are coming of age and processing events that are shaping their formative years. Of all generations living today, Gen Z

- Is the most educated and diverse

- Has dealt with the most chaos and trauma before their brains have fully developed by age 25

- Does not remember Americans being united. In fact, they have no favorite cultural memory the way Boomers have Woodstock and the civil rights movement, while Gen X has the Berlin Wall falling

In their lives, five events have transformed them:

- Occupy Wall Street, which highlighted economic inequality and the prevalence of money in politics

- 2016 election and Trump presidency

- 2017 Las Vegas shooting at the Route 91 Harvest Music festival, where 60 died and 867 were wounded

- 2018 Parkland shooting at Stoneman Douglas High School, where 17 died and 17 others were injured — the deadliest high school shooting in U.S. history that was documented in real time by student bystanders

- Darnella Frazier’s recording of George Floyd’s murder

And those were all before COVID-19.

“Gen Z is ... all about helping people rise together, which is empowering.”

The Harvard Public Opinion Project

The Harvard Public Opinion Project, which Della Volpe oversees, surveys young Americans ages 18 to 29 to determine the issues they value most. By analyzing partisan affiliation and racial identity and by including the stories of those polled to humanize the data, the Harvard Opinion Project provides a cohesive portrait of Gen Z that is presented to political leaders biannually.

The project originated with undergraduates two decades ago when Della Volpe found a disconnect between the young that didn’t translate to voting. He concluded that Gen Z’s shared fears involve survival —their own due to climate change and the threat it imposes on communities, as well as the survival of the Democratic party. Despite acknowledging an ongoing mental health crisis, Gen Z is not backing down from the challenges they face; instead, they are taking action.

Chelsea Jones grew up in Washington, D.C. and experienced hostility as a Black female reporter in Louisiana where the media was deemed the enemy and people “looked at you as threat or problem,” she states. “There were moments of being scared or feeling threatened [while I was] doing my job.” Speaking of her Zoomer generation, “We haven’t known a world without trauma — a world where we are not ingesting so many things at once.”

Jing-Jing Shen, also a member of Gen Z, notes the jarring juxtaposition of the internet and social media to connect people worldwide while depriving them of social connection. “The current label as the loneliness generation is indeed accurate.” She adds that the constant exposure to politics and the toxicity associated with it can make engaging with friends and online draining. Shifting to Zoom and virtual classes for a year and interacting with people through a screen versus face-to-face has made Gen Z appreciate the value of connection. “Gen Z has compassion and believes in increased access to healthcare for everyone who needs it. We are all about helping people rise together, which is empowering.”

Generational Differences

When Zoomers’ grandparents were their age, 82% of them didn’t vote. In 2018, Zoomers addressed their anxiety by voting — doubling their turnout from 2014. By 2020 college students were voting as the same level as average Americans. Forty percent of the current electorate consists of Gen Z and Millennials.

Scott MacKay, a self-described “crusty curmudgeon,” compared Zoomers with his generation of Baby Boomers who engaged in activism during the Vietnam era and experienced the rise of feminism, racial tensions, and the murders of John and Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. In terms of differences, Mackay cites the internet — a place where people are more likely to solidify their pre-established opinions and express them in ways they wouldn’t in person. He says that Boomers were taught to repress their feelings while Zoomers deal with them in healthier ways — a shift that he believes will lead to the betterment of society. Mackay also notes media’s shift in focus to being first at the expense of being right, the rise of celebrity talking heads and opinion-based shows and that are cheaper to produce than news reporting, and the decrease of civics education in schools as significant experiential differences between the two generations.

“From climate change to mental health access, we are championing a more equitable inclusive and hopeful future.”

Comparing Zoomers with Millennials, Della Volpe says that the two share similar values, but different levels of urgency. Zoomers want action now and are working inside and outside the system to achieve it. These actions are not confined to the ballot box; Zoomers are signing petitions and leading protests, but they are generally wary of performative activism and instead seek substantive activism. Jing-Jing notes that 37% of young Americans identify as politically active, 10 percentages points higher than a decade ago. “Zoomers believe in their own individual agency and that their individual actions do matter,” she states.

“Room for Optimism”

Despite affecting change through individual action, Gen Z often “doesn’t even know what the American dream is,” says Jones, because “first generation Americans, Black Americans, all we know is inequity. Now we finally have a voice … and are fighting in hope that we will know what that [American dream] is.”

Jing-Jing believes that Gen Z and Millennials will have a critical role in midterms. Although they don’t feel adequately represented, they acknowledge that their opinions are being considered (for example, the appointment of Supreme Court justice Kentaji Brown Jackson) and that there is, Jing-Jing states, “room for optimism.”

“From climate change to mental health access, we are championing a more equitable inclusive and hopeful future. It’s going to take some work, but we can get there.”